How the Allman Brothers Band’s ‘At Fillmore East’ Changed Everything

When 1971 began, the Allman Brothers Band may have been one of the best live acts in America, but career-wise they were just another mid-level group struggling to make a breakthrough.

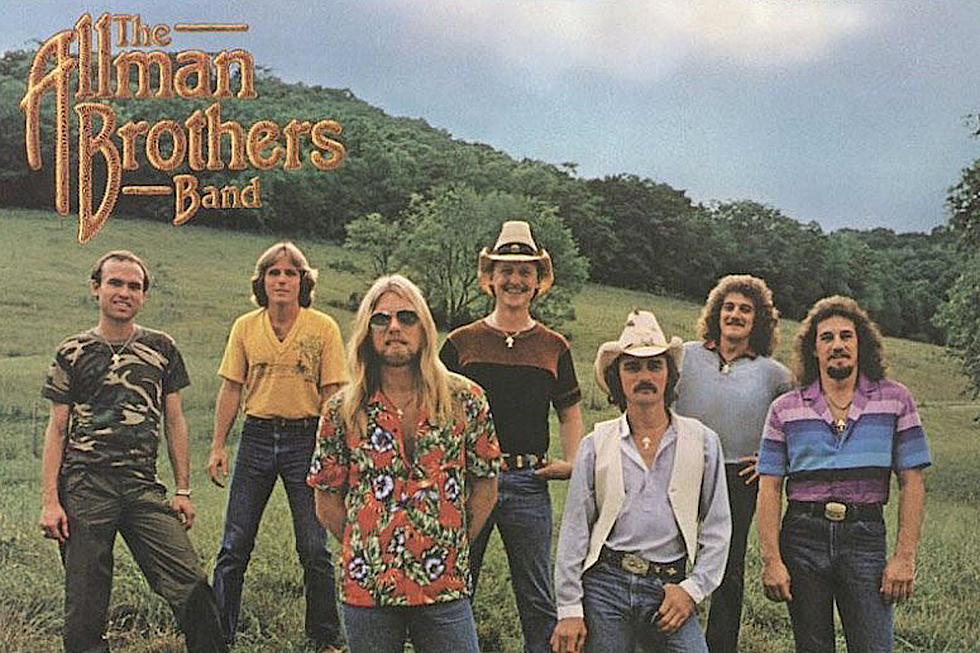

Their first two albums presented a young Southern blues-rock band with two guitar virtuosos in Duane Allman and Dickey Betts and a searing, soulful singer in Duane’s little brother, organist Gregg. But their studio efforts still hadn’t been able to capture the kind of fire the band could kindle on the stage, where their blues roots blended with jazz-influenced jams for a truly transporting experience.

The band had been running itself into the ground playing hundreds of dates a year just to keep even, earning fans on the road but not making much mainstream headway. The fact that multiple members had allegedly developed major substance abuse issues by that time surely didn’t help matters either. The follow-up to their second album, Idlewild South, was probably starting to look like a make-or-break proposition, especially since Duane had already collaborated with Eric Clapton in Derek and the Dominos by then, and could easily have gone off to other things if the band hit a wall.

The Allman Brothers understood the nature of their talents well enough by 1971 to determine that their next album should be a live recording. It would turn out to be the best decision the band ever made, both artistically and commercially.

Though the Allmans were on Georgia-based indie Capricorn Records, the label was distributed by Atlantic, who had helped set them up with renowned producer/engineer Tom Dowd for Idlewild South, and Dowd returned to helm the live recording. It probably didn’t take too much deliberation to decide on the ideal venue for the task.

In those days, Bill Graham’s Fillmore East and West were the standard-bearers for mid-size rock venues, and the Allmans had already ingratiated themselves to Graham; they’d played both clubs by 1971 and knew how well those concert halls suited the band’s sound. In due course, it was arranged for Dowd to man a 16-track console in a remote recording truck outside the Fillmore East to capture the Allmans’ performances on March 12 and 13.

The gravity of the moment was not lost on the band. After the first night’s show, they convened with Dowd to discuss which tunes they’d gotten good takes on, and which they’d have to load into the set list for the second night in order to take another crack at them. Their music may have been fueled by fearless improvisation, but offstage they were leaving as little to chance as possible. The band had even agreed between sets to take surprise guest saxophonist Rudolph “Juicy” Carter off the bandstand at Dowd’s behest, because of mixing issues.

Listen to the Allman Brothers Band Perform 'Whipping Post'

When At Fillmore East was released on July 6, 1971, it presented an entirely different Allman Brothers Band to the world at large. While the hardcore fans who’d been turning out to the shows were already well aware of the band’s jamming expertise, as far as the casual listener could tell from the first two studio albums, this was an ensemble that kept even its most adventurous excursions relatively concise for that era. So when the general public got an earful of what the Allmans were really all about onstage via the band’s first-ever live record, minds were blown.

Originally issued as a two-LP set, At Fillmore East featured only seven songs – not because it was skimpy on content but because it dutifully documented the band’s propensity for opening up ostensibly concise songs into breathtaking 20-minute jams.

The first LP shows off the blues-rocking side of the band’s sound. The Allman Brothers Band transformed a quartet of blues covers into something entirely their own, as the world got its first full view of what the band’s mighty twin-guitar team could do with barnstorming versions of Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues” and Elmore James’s “Done Somebody Wrong,” with wailing harmonica from guest Will Doucette on the latter. A simmering, slow-blues take on the T-Bone Walker standard “Stormy Monday” gives both Gregg’s growl and his smoky, jazz-inflected organ work a chance to shine. And a jumping, syncopated cover of the Willie Cobbs composition “You Don’t Love Me” maximizes every moment of its 20-minute length, especially when the rest of the band drops out to let Duane do his thing unaccompanied.

Sides three and four of the original At Fillmore East release were what really separated the band from the blues-rock pack. Consisting of three original tunes, they showed that the Allman Brothers Band had as much in common with Santana’s contemporaneous jazz-rock excursions as they did with the likes of Canned Heat, if not more. The group-written instrumental “Hot ‘Lanta” is a burning blues/jazz/rock amalgam that shows off the strengths of the whole sextet. The album’s final two tracks, however, would make rock history.

“In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” is extended to twice the length of its Idlewild South studio version, turning what was already one of the most finely crafted rock instrumental pieces ever written into something at once dreamily transcendent and thrillingly visceral. And “Whipping Post,” expanded from the five-minute track on the band’s debut into a roaring, fire-breathing 23-minute beast, is simply a force of nature. The churning, cyclical feel enabled by its odd time signature and the band’s double-drummer percolations is the perfect framework for Gregg’s epic tale of female perfidy. When he wails, “I’ve been tied to the whipping post,” you feel like he’ll be under the lash for eternity, or at least what feels like an eternity.

At Fillmore East took the Allman Brothers Band into the upper echelon of rock ‘n’ roll. It went gold quickly, and became a ubiquitous presence on rock radio forevermore. There have been numerous deluxe, expanded reissues, from two-CD packages all the way up to full-on box sets. It would eventually be hailed not only as one of the greatest live albums ever recorded, but simply one of the greatest albums overall. It helped put Southern rock on the map in the bargain, and solidified the approach the Allman Brothers Band would take from there on out.

Unfortunately, the Fillmore East closed its doors forever on June 27, 1971, but guess who was the headlining act for the farewell? More tragically, Duane Allman died on Oct. 29, 1971 at the age of 24 from injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident. Even though he became one of rock’s most maddening what-ifs, at least he stuck around long enough to make a piece of musical history.

Top 40 Blues Rock Albums

Tedeschi Trucks Band Discuss Their Influences

More From Classic Rock Q107