The Mystery of the Russian ‘Dr. No’ Review

One might have expected the Soviet Union to be decidedly negative toward the James Bond franchise as soon as it hit silver screens.

After all, Russian spies were often cast as the villains, even if they were sometimes just getting in 007’s way as he hunted down bigger game. And of course, the character himself represented everything Communists professed to hate about Western society.

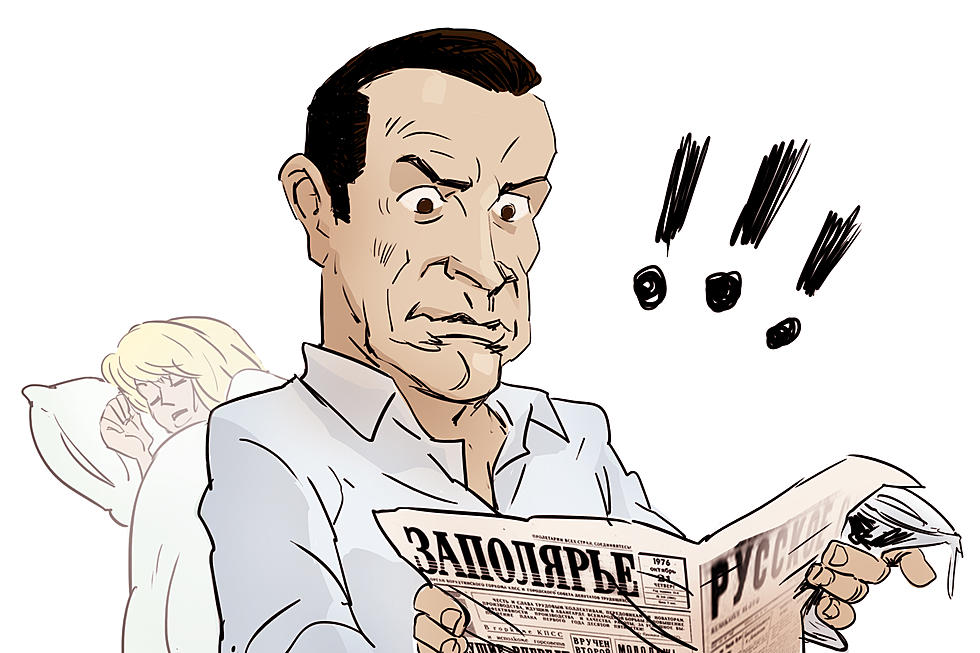

So it’s hardly a surprise that Izvestiya – the U.S.S.R.’s newspaper of record from 1917 until the bloc’s 1991 demise – was ready to slam Sean Connery’s portrayal of Bond when the first movie, Dr. No, premiered in the U.K. on Oct. 5, 1962. Much more of a surprise was that the review had been published five months earlier.

The original May 1962 article was titled “Love and Horrors,” the Spectator reports, and the author demanded: “Who’s interested in this rubbish?” They went on to describe Bond creator Ian Fleming, himself a former intelligence officer, as “a retired spy who has turned mediocre writer.”

Fleming enjoyed the roasting so much he attempted to have it printed on the back cover of his next Bond novel, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, only for the publisher to refuse. But a mystery remained: “Who at Izvestiya had managed to see the film so early – and how?" the Spectator report asks. “It is an example of cultural espionage worthy of a Bond novel itself.”

There could have been a Russian spy embedded in the movie production team, or among the wide range of media and publicity bodies involved in the project. But it’s just as possible that the piece was built from sheer speculation. After all, what would an official Communist mouthpiece be expected to say about a Bond movie?

In the British World War I comedy Blackadder Goes Forth, a British general describes German spies as “filthy Hun weasels fighting their dirty underhand war,” and in the next breath calls his agents “splendid fellows, brave heroes, risking life and limb for Blighty.”

Alternatively, someone might have simply read the book, guessing that the movie wouldn’t be significantly different, and just chanced to be right on a rare occasion. Its function was almost certainly more political than artistic, no matter what.

As the Spectator went on to report, a slightly more thoughtful reviewer named Maya Turovskaya later offered “a very shrewd and prescient piece of commentary on the Bond ‘brand’ that is as valid today” for the Russian magazine Novy Mir. She wrote: “Philistine pragmatism takes over in Fleming’s novels. They tend to be indiscriminate, to combine elements of all sorts of sensationalism – political action and thriller, science fiction and advertising brochure, a fashion magazine and nudist film.

“This, briefly, is the secret of the genre, of popularity in its modern shape,” Turovskaya added. “Had it not been for the screen, Bond would have been lost among all the other spy characters out there. A nobody. It was the film industry that made him a myth.”

The Soviet Union was forged in 1922 and collapsed nearly 70 years later. The 007 franchise reaches its 60th birthday later in 2022, but just like the Communist empire, the character has been subject to greater scrutiny and pressure as time passed. It remains to be seen if James Bond can survive longer than the political force that so often provided inspiration.

James Bond Movies Ranked

More From Classic Rock Q107